Molecular biomarkers in extrahepatic bile duct cancer patients undergoing chemoradiotherapy for gross residual disease after surgery

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

To analyze the outcomes of chemoradiotherapy for extrahepatic bile duct (EHBD) cancer patients who underwent R2 resection or bypass surgery and to identify prognostic factors affecting clinical outcomes, especially in terms of molecular biomarkers.

Materials and Methods

Medical records of 21 patients with EHBD cancer who underwent R2 resection or bypass surgery followed by chemoradiotherapy from May 2001 to June 2010 were retrospectively reviewed. All surgical specimens were re-evaluated by immunohistochemical staining using phosphorylated protein kinase B (pAKT), CD24, matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9), survivin, and β-catenin antibodies. The relationship between clinical outcomes and immunohistochemical results was investigated.

Results

At a median follow-up of 20 months, the actuarial 2-year locoregional progression-free, distant metastasis-free and overall survival were 37%, 56%, and 54%, respectively. On univariate analysis using clinicopathologic factors, there was no significant prognostic factor. In the immunohistochemical staining, cytoplasmic staining, and nuclear staining of pAKT was positive in 10 and 6 patients, respectively. There were positive CD24 in 7 patients, MMP9 in 16 patients, survivin in 8 patients, and β-catenin in 3 patients. On univariate analysis, there was no significant value of immunohistochemical results for clinical outcomes.

Conclusion

There was no significant association between clinical outcomes of patients with EHBD cancer who received chemoradiotherapy after R2 resection or bypass surgery and pAKT, CD24, MMP9, survivin, and β-catenin. Future research is needed on a larger data set or with other molecular biomarkers.

Introduction

Extrahepatic bile duct (EHBD) cancer is a rare malignancy [1]. Complete surgical resection provides the only possibility of cure, but it could be considered to a limited number of patients with early stage disease [2]. Between 50% and 90% of patients with bile duct cancer present with locally unresectable disease [3]. It has been known that the outcome of EHBD cancer is dismal. The 5-year survival rate is approximately 20% even after complete surgical resection [4]. Long term survivors cannot be expected after R2 resection or bypass surgery [5,6].

To improve outcomes, several researchers have tried to find out prognostic factors for EHBD cancer [7-18]. Especially, some molecular biomarkers were published as prognostic factors [12-18]. However, most studies were based on surgical series and patient population was heterogeneous especially in terms of adjuvant therapy employed.

The aim of this study is to analyze the outcomes of chemoradiotherapy for EHBD cancer patients with gross residual disease after surgery and to identify prognostic factors affecting clinical outcomes, especially, in terms of immunohistochemical results of molecular biomarkers such as phosphorylated protein kinase B (pAKT), CD24, matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP9), survivin, and β-catenin.

Materials and Methods

1. Patient population and treatment

After institutional review board approval, surgical and pathologic reports were reviewed. From May 2001 to June 2010, 21 patients with EHBD cancer underwent chemoradiotherapy or radiotherapy alone after R2 resection or bypass surgery.

As for surgical procedures, 19 patients had R2 resection such as palliative partial hepatectomy, hilar resection, bile duct resection and pancreaticoduodenectomy. Two patients had palliative bypass surgery.

Most patients (n = 18) were treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Concomitant 2 cycles of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) was given during radiotherapy. Among these patients, 15 patients continued maintenance chemotherapy after completion of chemoradiotherapy. Maintenance chemotherapy consisted of the median 5.5 cycles (range, 2 to 6 cycles) of 5-FU and leucovorin in 12 patients, 6 cycles of 5-FU in 2 patients and 8 cycles of 5-FU and cisplatin in one patient. Three patients received radiotherapy alone. The median duration from surgery to start of radiotherapy was 47 days (range, 35 to 145 days). The median radiation dose was 50.4 Gy (range, 40 to 55.8 Gy). Fraction size of each treatment was 1.8 or 2.0 Gy. Sixteen patients received continuous course radiotherapy, while 5 patients received split course radiotherapy which consisted of a total of 40 Gy at 2 Gy per fraction with 2-week planned rest after 20 Gy. Radiotherapy technique was 2-dimensional radiotherapy in 3 patients, 3-deminsional conformal radiotherapy in 16 patients and intensity modulated radiotherapy in 2 patients. The treatment volume encompassed gross residual disease, tumor bed and regional lymph nodes.

2. Immunohistochemistry

All 21 cases diagnosed as EHBD cancer were retrieved from the archives, which contained enough paraffin-embedded tissue for the study. After a review of the tumor sections of each case of cancer, one of the representative area of each donor block was punched out with a core of 4 mm diameter from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded blocks and arranged in new recipient tissue microarray (TMA) blocks using a trephine apparatus (Superbiochips Laboratories, Seoul, Korea).

The TMA blocks were sectioned at 5-µm thickness, transferred by water flotation, and dried at room temperature. Immunohistochemistry was performed on a Bond Max autostainer (Leica Microsystems, Bannockburn, IL, USA) using Bond Polymer Detection kit (Leica Biosystems). Immunohistochemical staining using antibodies to pAKT (rabbit monoclonal antibody; 1:100; Epitomics Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA), CD24 (mouse monoclonal antibody; 1:200; Thermo Scientific Korea, Seoul, Korea), MMP9 (rabbit polyclonal antibody; 1:100; Neomarkers, Fremont, CA, USA), survivin (rabbit polyclonal antibody; 1: 500; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA), and β-catenin (mouse monoclonal antibody: 1:500; BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA, USA) was done on all 21 cases automatically according to the manufacturer's protocol based on the conventional streptavidin-biotin-peroxidase method.

3. Immunohistochemical evaluation

Reading of imunohistochemical results was performed by one pathologist. For pAKT expression analysis, staining of cytoplasm or nucleus was considered positive (Fig. 1A). For CD24, MMP9, and survivin expression analysis, staining of cytoplasm was considered positive (Fig. 1B-D). For β-catenin expression analysis, staining of nucleus was considered positive (Fig. 1E).

4. Statistical analysis

Locoregional progression was defined as progression in primary site and regional lymph nodes, and distant metastasis was defined as progression in outside of locoregional area by follow-up imaging studies. Locoregional progression-free survival (LRPFS), distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS), and overall survival (OS) were counted from the date of surgery to the date of each event and calculated by the Kaplan-Meier method. Two-sided log-rank tests were used for the comparison of outcomes between groups. A p-value less than 0.05 in a two-sided test was regarded statistically significant. Data was analyzed using SPSS ver. 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

1. Patient characteristics

The median age of patients at surgery was 62 years (range, 24 to 79 years). Nine patients were female, and 12 patients were male. Most patients (n = 19) were of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status 0 or 1. Tumor location was hilar in 16 patients (Klatskin tumor) and non-hilar (common bile duct cancer) in 5 patients. Eight patients had regional lymph node involvement. In terms of Klatskin tumor, stage by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 7th edition was II in 4 patients, IIIA in 6 patients, IIIB in 5 patients, and IVA in one patient. T stage was T2 in 5 patients, T3 in 10 patients, and T4 in one patient. In terms of common bile duct cancer, stage was IB in 3 patients, II in one patient, and III in one patient. T stage was T2 in 4 patients and T4 in one patient.

2. Treatment outcomes and prognostic factors

The median follow-up duration was 20 months (range, 5 to 85 months). During follow-up, there were 15 cases of locoregional progression, 10 cases of distant metastases, and 14 cases of deaths. The actuarial 2-year LRPFS, DMFS, and OS rates were 37%, 56%, and 54%, respectively. The median LRPFS, DMFS, and OS were 15.5, 24.0, and 27.7 months, respectively (Fig. 2).

Survival curves of (A) locoregional progression-free survival (LRPFS), (B) distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS), and (C) overall survival (OS).

Age, gender, ECOG performance status, tumor location, nodal involvement, preoperative CA 19-9 level, type of operation and treatment were analyzed in univariate analysis for evaluation of prognostic significance of clinicopathologic features (Table 1). There was no significant prognostic factor on univariate analysis.

3. Immunohistochemical results

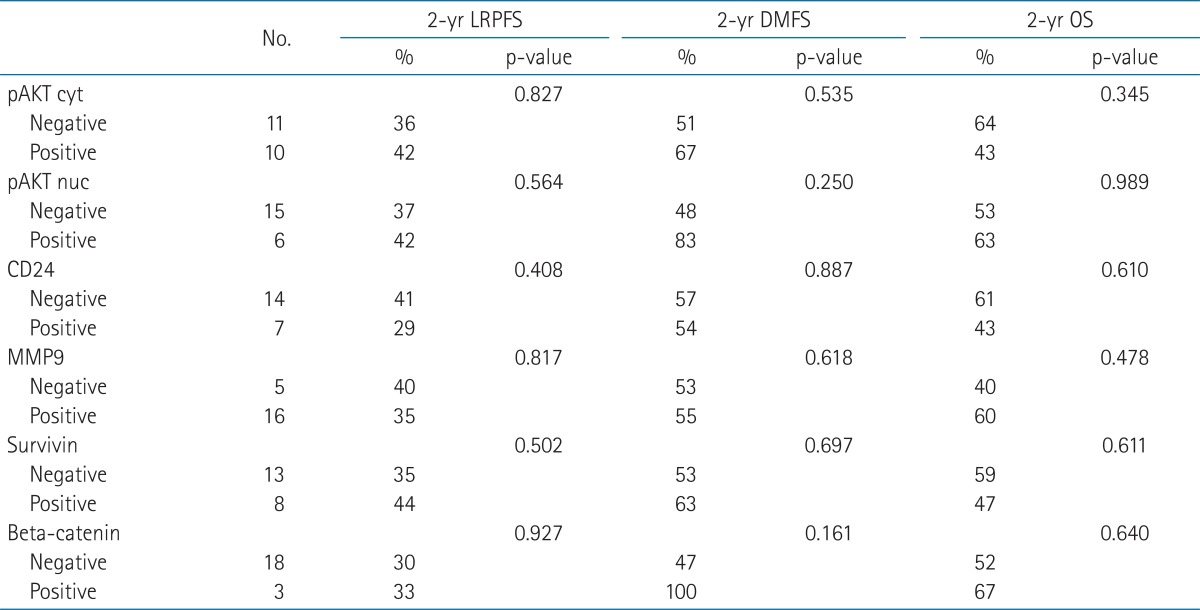

Ten patients had positive tumors for pAKT cytoplasmic staining, but 6 patients had positive tumors for pAKT nuclear staining. As for CD24, 14 patients had negative results. When MMP9 was evaluated, there were 16 patients with positive cytoplasmic staining. As for survivin, there were 8 patients with cytoplasmic staining. According to the expression of β-catenin, 3 patients were positive in nuclear staining. Table 2 shows univariate analysis of immunohistochemical results. There was also no significant prognostic factor.

Discussion and Conclusion

In the present study, the expressions of pAKT, CD24, MMP9, survivin, and β-catenin were not associated with the prognosis of patients with EHBD cancer who received chemoradiotherapy after R2 resection or bypass surgery.

It has been known that the AKT pathway plays a key role in the regulation of cellular survival, apoptosis, and protein translation, and that it has prognostic significance in a number of cancers. The AKT pathway is activated by phosphorylation, so pAKT means activated AKT [15]. Some reports described AKT expression in bile duct cancers [16,19,20]. Chung et al. [15] reported pAKT expression was increased in 84.2% of 221 cases, and high pAKT group showed poor survival rate than low pAKT group (p = 0.06). In the study by Tanno et al. [19], 16 of 19 cases were positive for pAKT, and pAKT expression resulted in decreased radiosensitivity in the cell study. On the contrary, Javle et al. [20] suggested that high expression of AKT was correlated with improved survival in 24 cases of cholangiocarcinoma in multivariate analysis, and there was a significant association between AKT and pAKT in tumor tissues by Pearson correlation test.

CD24 is an adhesion receptor on activated endothelial cells and platelets and has been known to be associated with tumor proliferation, cell adhesion, motility, invasion, and apoptosis [21,22]. CD24 expression has been suggested as an adverse prognostic marker in several malignancies including cholangiocarcinoma. Agrawal et al. [23] studied 22 consecutive patients with cholangiocarcinoma, and the median survival of patients with high expression of CD24 was significantly shorter than those with low expression (p = 0.02). Among patients treated with chemotherapy, patients with low expression of CD24 had the median survival of 163 months, but it was only 17 months in patients with high expression (p = 0.04). This trend was sustained to patients treated with radiotherapy, and the median survival of low expression of CD24 versus high expression was 52 months versus 17 months (p = 0.08). In the study of 34 cases of resected cholangiocarcinoma by Keeratichamroen et al. [22], patients with high expression of CD24 had the median survival time of 9 months, whereas it was 24 months in patients with low expression (p = 0.007).

MMP9, a member of the matrix metalloproteinase, which digest the extracellular matrix required for cancer cell invasion [24]. Shirabe et al. [25] analyzed 37 patients with surgically resected intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, and revealed that MMP9 expression was a prognostic factor associated with inferior survival. In contrast, Itatsu et al. [17] evaluated 66 cases of surgically resected EHBD cancers to find out the relationship between each subtype of MMPs and clinical outcomes. They proposed the expression of MMP7 was an unfavorable prognostic factor, but not for MMP9.

Survivin, an inhibitor of apoptosis protein, is not expressed in differentiated normal adult cells, but the overexpression was reported in bile duct cancers by several investigations [18,26-28]. Qin et al. [18] reported the significant difference of the mean survival time between patients with negative expression of survivin and positive expression (43.5 months for negative vs. 21.1 months for positive, p < 0.01) in EHBD cancer. Javle et al. [28] also suggested survivin expression as a poor prognosticator in cholangiocarcinoma.

β-catenin has been known as an oncogene in many types of cancer, such as medulloblastoma, colon, thyroid, breast cancer and liver [29,30]. There was a study on the association between β-catenin and ampullary cancer, one of the periampullary cancers. In the study by Hsu et al. [31], loss of β-catenin expression was associated with disease recurrence on multivariate analysis. However, the prognostic value of β-catenin in EHBD cancer has not been reported.

In the present study, none of the 5 molecular biomarkers were correlated with the clinical outcomes. Given the retrospective nature of the study, the potential for selection bias cannot be excluded. Moreover, the tumor burden seems to be highly heterogeneous from the small gross residual disease to the bulky tumor, although the study population is relatively homogeneous in respect to the adjuvant treatment, that is, chemoradiotherapy. Also, small sample size might fail to detect the small significant difference.

In terms of clinical outcomes, the results of our study seem to be better than those of the previous studies (Table 3). However, patient population as well as tumor burden is highly heterogeneous among those studies including ours and moreover, the patient number is quite small. Further study with a larger cohort is needed for more understanding of this rare clinical situation.

In conclusion, it was impossible to find out prognostic value of pAKT, CD24, MMP9, survivin, and β-catenin in patients with EHBD cancer who received chemoradiotherapy after R2 resection or bypass surgery. Future research is needed on a larger data set or with other molecular biomarkers.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by KOSRO Young Investigator Fund.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.