Endoscopic findings of rectal mucosal damage after pelvic radiotherapy for cervical carcinoma: correlation of rectal mucosal damage with radiation dose and clinical symptoms

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

To describe chronic rectal mucosal damage after pelvic radiotherapy (RT) for cervical cancer and correlate these findings with clinical symptoms and radiation dose.

Materials and Methods

Thirty-two patients who underwent pelvic RT were diagnosed with radiation-induced proctitis based on endoscopy findings. The median follow-up period was 35 months after external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) and intracavitary radiotherapy (ICR). The Vienna Rectoscopy Score (VRS) was used to describe the endoscopic findings and compared to the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC)/Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) morbidity score and the dosimetric parameters of RT (the ratio of rectal dose calculated at the rectal point [RP] to the prescribed dose, biologically effective dose [BED] at the RP in the ICR and EBRT plans, α/β = 3).

Results

Rectal symptoms were noted in 28 patients (rectal bleeding in 21 patients, bowel habit changes in 6, mucosal stools in 1), and 4 patients had no symptoms. Endoscopic findings included telangiectasia in 18 patients, congested mucosa in 20, ulceration in 5, and stricture in 1. The RP ratio, BEDICR, BEDICR+EBRT was significantly associated with the VRS (RP ratio, median 76.5%; BEDICR, median 37.1 Gy3; BEDICR+EBRT, median 102.5 Gy3; p < 0.001). The VRS was significantly associated with the EORTC/RTOG score (p = 0.038).

Conclusion

The most prevalent endoscopic findings of RT-induced proctitis were telangiectasia and congested mucosa. The VRS was significantly associated with the EORTC/RTOG score and RP radiation dose.

Introduction

It has been reported that approximately 5%-20% of patients develop chronic gastrointestinal complications after pelvic radiotherapy (RT), although the value varies according to the measurement scale [1,2]. Chronic proctitis has a significant effect on quality of life and is one of the most important toxicities among several possible complications after pelvic RT [2]. Direct inspection using endoscopy is thought to enable the best estimate of rectal mucosal damage.

Recent data have shown correlations between rectal mucosal damage and dose-volume effects or rectal symptoms in patients who underwent pelvic RT for prostate cancer [3,4]. However, despite proctitis being a major toxicity after pelvic RT, it is not well known that the relationship between endoscopic findings and radiation dose following pelvic RT and intracavitary radiotherapy (ICR) for cervical cancer.

In the current study, we retrospectively evaluated the relationships between endoscopic findings and mucosal abnormalities, the severity of clinical symptoms, and the absorbed dose at the rectum in patients with cervical cancer who were treated with pelvic RT, which included external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) and ICR, and who were then proven to have rectal mucosal damage on endoscopic examination.

Materials and Methods

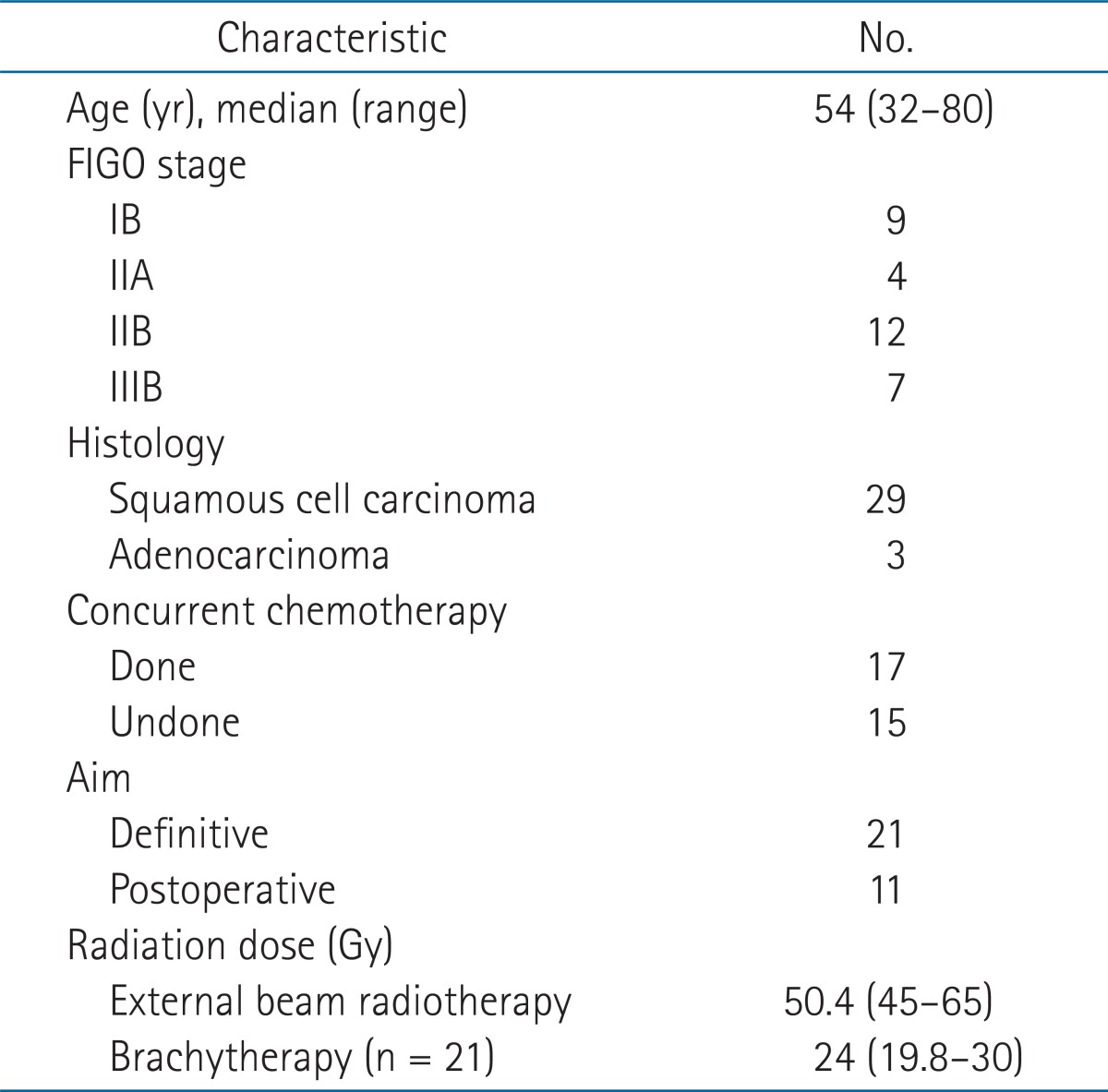

From September 1995 to July 2009, 1,413 patients with uterine cervical cancer were treated with definitive or postoperative RT at Samsung Medical Center in Seoul, Korea. Of these patients, 112 patients underwent endoscopy following RT for bowel symptoms evaluation at 78 patients and for health screening at 34 patients. Of these patients, 32 who were diagnosed with rectal mucosal damage were analyzed in this study. Of the 32 patients, 25 patients underwent endoscopy to evaluate any gastrointestinal symptoms, of which the patients complained, and last seven patients underwent endoscopy as health screening.

The patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. The median patient age was 54 years (range, 32 to 80 years) and the follow-up period was a median of 35.4 months (range, 2 to 136 months). The median interval between the start of RT and the development of proctitis was 19.5 months (range, 2 to 114 months).

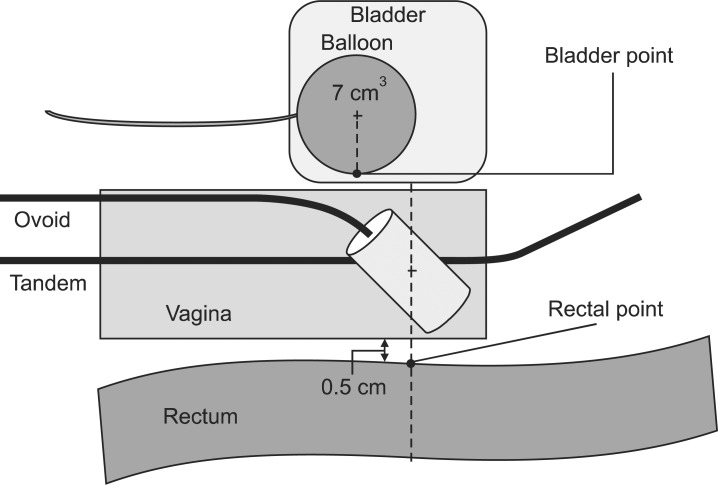

All patients underwent EBRT with 3-dimensional (3D) conformal or conventional 2D planning. EBRT was delivered with a 15 MV X-ray using two or four fields. The RT dose was administered in daily fractions of 1.8 Gy, five days per week, up to a median dose of 50.4 Gy (range, 45 to 65 Gy). High dose rate (HDR)-ICR was performed using a 192Ir remotely controlled afterloading system in 21 patients who had definitive RT. Midline shielding with 2 cm block around tandem at anterior/posterior ports was performed at the last three fractions. The dose of HDR-ICR to point A was 24 Gy and was delivered in 4 Gy fractions three times per week. The rectal dose was calculated at rectal reference points (RP) as defined in the International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements Report 38 (ICRU 38) (Fig. 1). The remaining 11 patients had undergone postoperative RT. The RT dose analysis was conducted in 29 of the patients because data pertaining to the rectal point dose according to the ICR plan could not be obtained for 3 patients. The biologically effective dose (BED, α/β = 3) was calculated from the ICR dose at the RP and the dose of ICR at the RP plus EBRT (total BED = BEDEBRT + BEDICR, where a value of 3 was used for late responding tissues), respectively. In patients who underwent postoperative RT, the BED was obtained from the dose of EBRT only. The correlation between the BEDICR, BEDtotal at the RP and the grade of rectal mucosal damage as determined by endoscopy was evaluated.

Localization of bladder and rectal point from the International Commission on Radiation Units and Measurements Report 38 (ICRU 38). On the lateral radiograph, the rectal point is located on a line drawn from the middle of the ovoid source, 5 mm behind the posterior vaginal wall. The posterior vaginal wall may be visualized using radiopaque gauze for vaginal packing. The bladder point is obtained on a line drawn anteroposteriorly through the center of the balloon at the posterior surface.

All patients were evaluated for symptomatic complications by careful retrospective inspection of the medical records. Complications from RT were graded according to the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC)/Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) morbidity score for the rectum [5]. The endoscopic findings were analyzed retrospectively based on the description of the findings or the authors' interpretation of the photo taken during endoscopy. Abnormal endoscopic findings were classified according to the Vienna Rectoscopy Score (VRS) for systematic description of the findings (Fig. 2) [3]. This study was approved by the ethic committee of Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine (IRB No. SMC 2012-09-081).

Endoscopy findings illustrating the different grades of telangiectasia. (A) Normal mucosa, (B) grade 1 telangiectasia with single lesion, (C) grade 2 telangiectasia with multiple nonconfluent lesions, (D) grade 3 telangiectasia with multiple confluent lesions.

Fisher's exact test was used to analyze the relationship between the VRS and the EORTC/RTOG score and between the VRS and the BED at the RP calculated from the ICR and EBRT plan. Statistical tests were performed using PASW ver. 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A p-value of 0.05 or less (two-sided test) was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

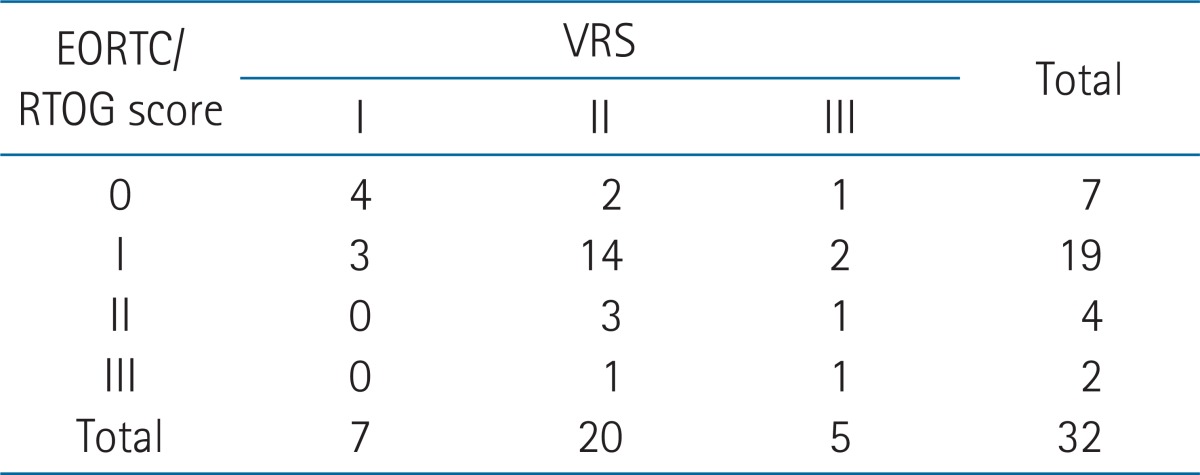

The most frequent symptom was bleeding, occurring in 21 patients (72.4%), 16 of which were scored as grade 1 according to the EORTC/RTOG criteria (Table 2). Endoscopic findings were congested mucosa in 20 patients (62.5%; five with grade 1, eleven with grade 2, four with grade 3), telangiectasia in 18 patients (56.3%; three with grade 1, fifteen with grade 2), ulceration in five patients (15.6%; three with grade 1, one with grade 2, two with grade 3 ), and stricture in one patients (3%; grade 1).

The VRS was significantly correlated with the EORTC/RTOG score (p = 0.038). Twenty-five patients had morbidity scores greater than grade 2 (Table 3). There were seven patients who developed endoscopic abnormalities without rectal symptoms. One of these patients did not complain of any abnormal symptoms at follow-up despite having grade 3 congested mucosa.

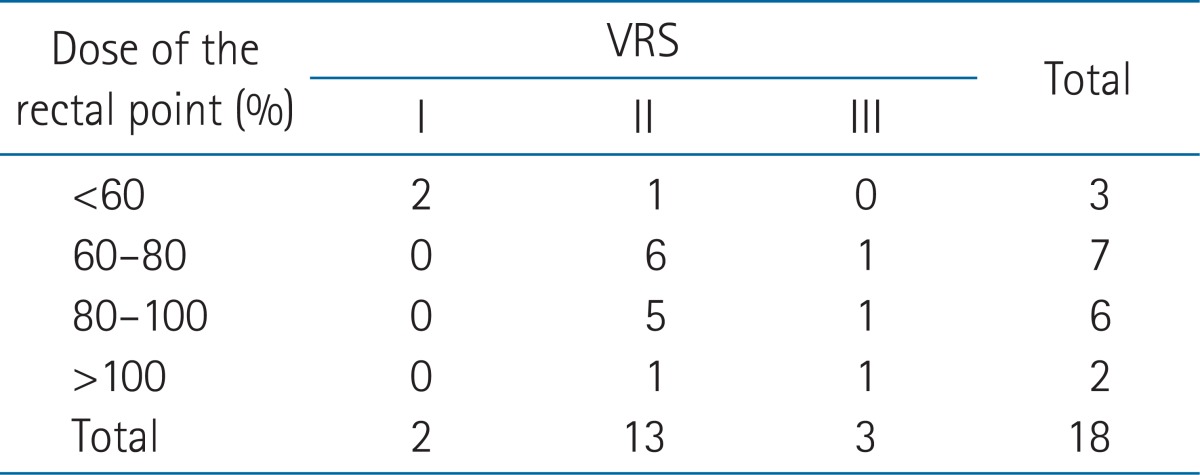

The dose at the RP was a median of 18.4 Gy (range, 9.8 to 26.6 Gy), as measured from the ICR plan in 18 patients who had ICR. The median value of the RP ratio (the dose at the RP/the prescribed [point A] ICR dose) was 76.6% (range, 40.7% to 132.2%). There were positive correlations between the VRS and radiation dosimetric parameters of ICR including the ICR rectal point dose, the RP ratio (BEDICR: r = 0.829, p < 0.001; RP ratio: r = 0.821, p < 0.001) (Table 4). BEDtotal (EBRT plus ICR dose) was also correlated with the VRS in 29 patients who had ICR and/or EBRT (r = 0.639, p < 0.001).

Twenty-four patients who had no RT-induced rectal symptoms or minor complications received no specific treatment and were monitored closely. On the other hand, eight patients who complained of persistent symptoms were treated using endoscopic coagulation or medical therapies (sucralfate or rectal steroid enema). All but one patient experienced an improvement in symptoms without supplemental therapy. The rectal dose was high in this patient (RP ratio, 125%) and slight rectal bleeding continued even after sucralfate enema and endoscopic coagulation.

Discussion and Conclusion

Chronic rectal symptoms, including rectal bleeding, loose stools, urgency, abdominal pain and tenesmus, may occur in patients who receive pelvic RT over several years, with intermittent bleeding being the most common [3,6-8]. Overall, it is estimated that up to 20% of pelvic RT patients develop chronic rectal complications after treatment [7,9]. It has been reported that 11% of patients develop rectal complications after RT for cervical cancer at our institution [10]. In this study, of the 112 patients who underwent sigmoidoscoy following RT, 32 patients (28.6%) had RT-induced rectal mucosal damage. A relatively high incidence of rectal mucosal damage on endoscopy is thought to be due to a large number of patients who underwent endoscopy to evaluate the any bowel symptoms, especially rectal bleeding.

Hu and Wallner [11] reported spontaneous healing of minor radiation-related bleeding and no obvious difference in the resolution rate between the treatment group and the non-treatment group. For patients with minor bleeding and no hemodynamic or hematological sequelae, reassurance and simple follow-up may be all that is required [1,12]. In more severe cases, oral therapy, rectally instilled therapy, thermal therapy and hyperbaric oxygen may be useful [13-15]. However, evidence-based therapies are lacking for chronic radiation-induced proctitis [1]. In this study, rectal instillation therapies or endoscopic therapies using coagulants were given only to patients who had massive proctorrhagia and no specific treatment was given to patients with minimal or no hemorrhage. Rectal symptoms in 20 out of 21 patients with hemorrhaging improved after simple observation.

Abnormal endoscopic findings after pelvic RT include congested mucosa, telangiectasia, ulceration, stricture and necrosis. The probability of endoscopic abnormality development after pelvic RT is not known because there have been no prospective studies involving routine follow-up endooscopy in all patients who receive pelvic RT. However, one study reported endoscopic abnormalities in 68% of patients who voluntarily underwent sigmoidoscopy after pelvic RT for prostate cancer [4,16]. Endoscopic follow-up studies have shown that late rectal mucosal changes improve over time with a peak at 12 months after treatment [17,18].

Rectal symptoms are not always suggestive of radiation-induced proctitis. In endoscopic studies in patients with bleeding, non-radiation-induced disease including recurrent or new tumors, high-risk adenoma, polyps, diverticular disease, or hemorrhoids were found in 34%-56% of patients [19,20]. Also, it has been reported that endoscopic abnormalities such as telangiectasia and congested mucosa are not always suggestive of rectal symptoms. Several researchers have reported that 20%-52% of patients with mucosal damage had no obvious symptoms [3,19,21]. Routine follow-up endoscopy for all patients may not be necessary because the rate of endoscopic abnormality exceeds the rate of rectal symptoms and symptoms often resolve spontaneously over time.

Predisposing factors related to chronic proctitis include previous acute proctitis, a low body mass index, previous abdominal surgery, concomitant use of chemotherapy, the presence of co-morbid conditions, RT fractionation, and the RT field and RT dose of ICR [14,22-28]. Several studies have analyzed the correlation between the radiation dose and the development of proctitis after pelvic RT. These studies have suggested rectal doses >80 Gy, BED at the RP >125 Gy3, ratio of the rectal dose to the point A dose >70%, and the measured rectal BED >110 Gy3 as predisposing factors for proctitis [24,25,29,30]. The radiation dose at the RP, as defined by ICRU, was demonstrated to be a prognostic factor for proctitis in many investigations and is widely used as a dose constraining parameter in the ICR plan. In this study, the dose at the RP was used to predict rectal complications and was correlated with the VRS, especially BEDICR. However, several investigators have suggested that dosimetric parameters other than the RP, such as proximal rectal dose and dose-surface histograms, could be more useful for predicting late rectal complications [31,32]. Although the dosimetric parameters used as prognostic factors for proctitis vary, most studies suggest that high radiation doses at the rectum increase the probability and severity of proctitis [24,25,29-32].

It has been documented in previous studies that VRS correlates with the total dose in 0.1, 1.0, 2.0 cm3 of the rectum and with the dose at the ICRU rectal point [21,33]. In this study, dose-volume analysis was not performed because all patients underwent fluoroscopy-based ICR planning. However, the RP ratio, BEDICR, and BEDICR+EBRT were significantly associated with the VRS and the ICR dose was more strongly correlated with the VRS than the total dose from EBRT plus ICR.

This study had a limitation on small number and selection bias of enrolled patients from retrospective design. Only the patients who turned out to have rectal mucosal damage from endoscopy, were analyzed. Thus, the actual rate of radiation induced injury in asymptomatic patients following RT for cervix cancer could not be drawn from this study. However, our results demonstrated that the grade of symptoms and radiation dose were significantly related to the severity of mucosal damage in patients with endoscopy abnormality in common with previous study of prostate cancer. To confirm our results, a prospective study with more large cases will be needed.

In conclusion, telangiectasia and congested mucosa were the most prevalent endoscopic findings of RT-induced proctitis. There was significant coherence between the VRS and EORTC/RTOG scores and between the VRS and the radiation dose. In particular, BEDICR was strongly correlated with the severity of mucosal damage and thus could be considered a prognostic factor for proctitis.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.